This is an account of two well-used student tenor banjos I recently adopted for a demonstration, plus an account of how I put them to use in a workshop at a local festival. It’s provided here as a background to anyone considering a similar experiment with 4-strings, and for your enjoyment period.

Anyone reading my articles must think I “churn” banjos, buying and selling all the time. I’ve actually met guys who do that. But in my case, I mostly found a “no brainer” deal on a model or type of banjo I was curious about, tried it out, wrote about it, but wasn’t quite satisfied, then found a better banjo on a “no brainer” deal, upgraded, wrote about the upgrade, and sold off the old one. For the kinds of music I play, I need at least one good backless banjo, at least one good Bluegrass banjo, and at least one good six-string. Yes that may seem like a lot of banjos, but they aren’t any more interchangeable than, say, an acoustic guitar, a Stratocaster, and a bass guitar. I confess, though, that I also have a “beach” 5-string and a “beach” 6-string, which doubles as my travel guitar, since so-called travel guitars all have such short scales and strange necks. Okay, so that’s five banjos. Plus the one I thought I had sold and the guy bailed, but which I’ll put back on the market again after some other things settle down. Okay, so that’s six banjos. . . .

I was recently asked to provide a “live workshop” version of my “What Kind of Banjo Do I Want?” article for a local festival. The article includes a description of the most common 4, 5, and 6-string banjos. Though I have 5- and 6-string banjos onhand, I haven’t owned a 4-string banjo since the mid-1960s. Well, I figured, if nothing else, the rising interest in Irish banjo (as per Mumford & Sons and similar groups) is a reason to bring one of those to the workshop.

Then I couldn’t find one cheap locally, which was surprising, since they’re usually pretty plentiful. Folks keep finding them in their uncles’ estates or whatever, since they were once the most popular kind of banjo, then realizing that hardly anyone plays 4-strings any more and selling them cheap.

I saw an old Aria 4-string on eBay and sent in a low-ball offer, since time was getting short. Aria was a Japanese company that made “knockoffs” of good American instruments in the 1960s, and many of their knockoffs were better than you’d expect. However this one was obviously very early in the evolution of their instruments. It had the old Harmony-style open guitar tuners complete with the little plastic collars sticking out the front to “dress it up” a little. It also had brackets holding the resonator on, a sure sign of a cheap banjo. I suspected from the photos that the pot was cast aluminum, a dodge that cheap banjos had been using for decades by 1960. Well, if it was playable at all, it would work for the demonstration. The offer was accepted, and soon it was on its way, cardboard case and all.

Then, a local fellow listed a better Aria 4-string banjo on on Craig’s list for a better price than I’d paid for the cheapy. I figured I might as well get that one too. That way I could tune one as a Jazz tenor (ADGC, counting from your toes up) and one as an Irish tenor (EADG, counting the same way).

The “better” Aria was probably made in the 1970s. Although it was made in Korea instead of Japan, I could tell from the photos it was an “upgrade” to the Japanese one. Except for the planetary tuners and the real wood pot, several of the apparent “upgrades” were cosmetic, though. For example, the resonator flange, an improvement on the brackets on the cheaper version, was stamped, not cast, as they are on better banjos. So it looked fancier. I was hoping, at least that it was made better.

The seller of the second one cross-examined me somewhat before he let me come to see it. Turns out he’d had a lot of folks call thinking they were going to get a fancy Bluegrass banjo cheap. No tone ring, only one coordinator rod, but most importantly, not enough strings. The truth is that I’ve heard Irish 4-string pickers who were so fast with a flatpick that I could barely tell they weren’t, technically, playing Bluegrass. But folks here in Southwest Ohio aren’t impressed by that sort of thing – they want to see someone who can plant his pinky and ring finger on the head just north of the bridge and do the rest with fingerpicks.

I assured the seller I knew what I was buying and we arranged to meet up. Again, the banjo is not as professional as the fancy engraving and inlays would have you believe, but it’s pretty solid. A no-brainer under the circumstances.

When I got a chance to get the banjos out and work on them, I removed the resonators, tuned them up to check and do a preliminary adjustment on the action, removed the strings, cleaned them up somewhat, and oiled the fretboard. Then I replaced the strings, set the bridge, and started fine-tuning the action.

Tuning Up the Harmony Clone

Here’s an oddity; the older, cheaper model had 20 frets, as if the manufacturers couldn’t decide whether they were making a Plectrum banjo (21 frets) or a 19-fret Tenor banjo. I tuned it as I would a 19-fret Tenor eventually, but I thought that was interesting.

The tuners on the cheapy were sloppy, like those on many old Kay, Harmony, and Silvertone banjos and guitars. When you need to tune down a little, you can’t just loosen the string a little, like you do with better tuners – you have to loosen it half a turn or more, then come back up. Otherwise, there is so much slack in the gearing that the peg won’t turn and loosen the string. You CAN tune such a beast, you just have to remember its quirks.

The neck on the cheapy had more bowing on one side than the other, ALWAYS a bad sign. But by adjusting the coordinator rod and neck adjustment rod, I WAS able to get the strings in the same time zone as the fretboard, and get reasonable action up most of the neck. Then I did something I never do, I experimented with strings to try to get a good sound-to-playability blance. In part, the experimentation was necessitated by the fact that the neck kept “readjusting” itself and needing a little more tweaking over a several hour period, and that was hard on the strings.

Finally, though, I stumbled upon a combination of string gauges and neck setup that left the thing playable, if not as loud as it would have been with heavier strings. A day later, it only needed a slight tuning to be in tune, and it STAYED in tune for more than an hour during a rainstorm at a festival, protected from the weather by only one of those pop-up shade thingies they use at tailgate parties.

The newer, Korean 4-string had recently been set up and played by its previous owner, and needed only very minor adjustment. The owner had also given me a new set of Deering Irish Tenor Banjo strings. So that should have been a piece of cake. Ironically, though it was in better shape when I got it, it didn’t hold a tune quite as well as the cheapie, at least not at first.

Saturday, August 13, I loaded up a ton of banjos. Well, not a ton, technically. Two six-strings, four five-strings, and two four-strings. Okay, that’s eight banjos.

Saturday, August 13, I loaded up a ton of banjos. Well, not a ton, technically. Two six-strings, four five-strings, and two four-strings. Okay, that’s eight banjos.

Then I drove to the Madden Road Music Festival, a once-a-year family-run affair about twenty miles east of Urbana, Ohio.

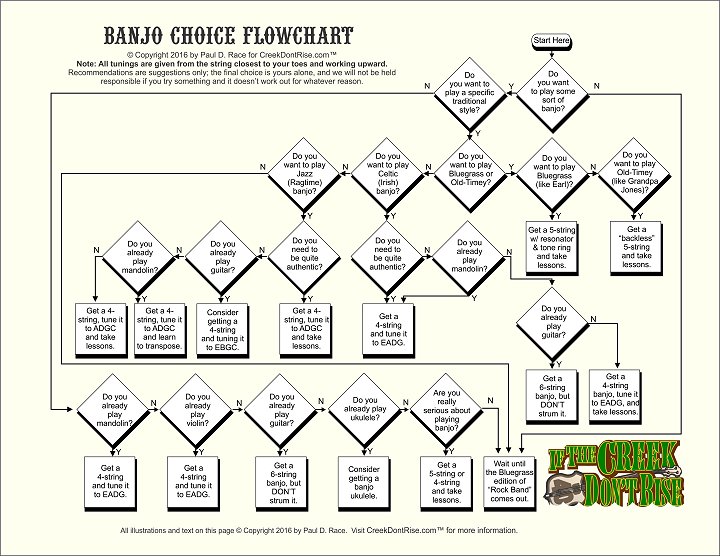

I had printed off my Banjo Choices flowchart, which should help people who know nothing about banjos and think they’d like to get one make more informed choices. (For a high-definition printable version, click on the following graphic.)

On the back side of the same sheet, I had printed my “Anatomy of a Professional Banjo” mini-poster. I was planning on showing what a tone ring is, and so on, but this way, they’d still have a reference to come back to later if questions came up.

On the back side of the same sheet, I had printed my “Anatomy of a Professional Banjo” mini-poster. I was planning on showing what a tone ring is, and so on, but this way, they’d still have a reference to come back to later if questions came up.

I had also printed up directions from Google Maps. Theoretically it should only have taken a half hour or so to get there, but a heavy rain came up almost as soon as I got on the road. And once I got out into the middle of nowhere, the Google Maps direction had me turn the wrong way at one of the intersections.

Worse, several of the roads I passed subsequently had no road signs – a frequent problem in rural Ohio, though I don’t know why. So I wasn’t even sure that if the directions had been correct I would have turned on the right roads subsequently. Handy hint: If you ever decide to go to the Madden Road Music Festival, use a GPS to get there. 🙂

When I realized I had taken a wrong turn, I pulled over and programmed everything into the Samsung that AT&T had just “upgraded” because the one I liked would no longer hold a charge. I’m still learning the new phone. But it did get me to the festival eventually, albeit a half hour later than I expected.

As it turned out, I hadn’t missed anything to speak of, except a flurry of tent-setting up and tarp rolling-out. The rain had almost stopped when I arrived, and people were starting to set up to play again.

At one point, one of the acts had started to set up, then the rain started again. While everyone was standing around waiting for the rain to clear, I pulled out my Goodtime Classic Special Backless (the one with a tone ring and the sparkle of a mountain stream) and played several Bluegrass style instrumentals. Hopefully that entertained at least a few people and didn’t annoy too many. In retrospect, I should have led some singalongs, but I haven’t been one of those “I have my guitar with me so I’m in charge” people since the 1980s. Then the rain cleared again.

I met up with the people I was supposed to meet up with, especially Daniel Dye, who was spearheading the whole thing and providing music later. I also met up with many other nice folks. I made a point of hearing most of the acts I had really wanted to hear, including Jill and Micah (below left), the Willow Wacks, and the Kurtz sisters (below right). The duo Sweet Betsy started playing just as I was setting up, so, though I could hear them, I couldn’t watch them.

|

|

When it was approaching my turn to present, I cleared out the area where I was going to be setting up, set out all my banjos on top of their cases and gig bags, and tuned each one, which was a bit of a challenge with some of them since the humidity was outrageous.

Then I gave a brief history of the banjo, explaining how it came from Africa, why a drum-like construction replaced the original gourds, why the drone string appeared, then disappeared, and why tone rings and resonators got added, and why the drone string came back in force eventually. All while showing the various banjos that represented the eras I was describing.

I passed out a few. In some cases, I showed the difference between the sheer weight of student and professional resonator banjos by handing people the lighter one first then handing them the pro banjo. I don’t THINK anybody dislocated their wrists or anything, but a few folks’ eyes got big.

The tenors came first in the demonstration, since a century ago, they were the most popular banjo. They lost the drone string because Jazz bands played in so many keys and changed chords so often that the drone string, frankly didn’t add anything, and it mostly just got in the way. Then their tuning changed from traditional banjo tuning (DBGC, counting from the string closest to your toes and going up) to viola tuning (ADGC) to facilitate being able to play the same song in many different keys easily. This part of the demonstration started with the cheapie, including my rendition of “Five Foot Two,” which I’m sure would have been Grammy-nominated if anyone had captured the thing on video. Then I held up other banjos to demonstrate what a tone ring was and explained that tone rings and resonators first really found a home in Jazz, where keeping up with horn sections in volume was critical.

After going back to the backless 5-strings to explain “Old-Timey” music and the Folk Revival Movement, I picked up the other tenor to explain how Irish banjo developed its own style and tuning in the mid-20th century. Sadly, I could not do the thing as much justice as I did the Jazz tenor, since I’m not in practice playing true Irish-style leads on instruments tuned in 5ths.

I demonstrated the Bluegrass five-string (a Deering Sierra) while explaining that Scruggs’ picking style often involved picking one note at a time, so Bluegrass pickers needed even more volume than Jazz banjos, and happily borrowed the Jazz banjo’s tone ring and resonator.

I also demonstrated my six-strings, explaining that they were not just a cop-out for guitar players who want to play a banjo without learning anything. They are also a century-old-instrument once used in Jazz as well. I also used my Deering Deluxe six-string to demonstrate that you can’t just strum a resonator/tone-ring version with a flatpick like you would a guitar – the notes sustain too long. Then I demonstrated lead-picking and explained that both the Irish tenor and 6-string banjo had a lower range than standard 5-string banjos. I also explained that I liked the gutsy, almost Dobro-like sound of those low strings, as long as you pick them one at a time.

Afterward there was a question and answer session, plus a lot of folks trying banjos out. One young guitar player figured out some things on a five-string pretty quickly. So I showed him the C and Dsus4 chords and he had a great time, although he wasn’t exactly using a traditional right-hand technique. A nice young lady fell in love with the backless six-string (a Jameson/Davison that I had taken the resonator off and more-or-less rebuilt to make playable). And several other folks tried one or the other. In fact, they were still going strong when the next band was supposed to be playing on the main stage, just 60 feet away, so one of the festival facilitators asked me nicely if we could shut it down. I collected all the banjos, thanked everybody for listening, and answered a few more questions while the crowd filtered out to hear the next band.

After I got the banjos all into their respective cases, I listened to Dan Dye’s “Miller Road Band” set before I packed up. There was going to be music after that, but, based on my experience getting to the festival, I decided to head home while it was still at least a little bit light out.

After I got the banjos all into their respective cases, I listened to Dan Dye’s “Miller Road Band” set before I packed up. There was going to be music after that, but, based on my experience getting to the festival, I decided to head home while it was still at least a little bit light out.

Now that the banjos are all home safe and sound, what will I do with the tenors? I plan to loan the better one (which is tuned like an Irish banjo) to a friend who plays mandolin and plays in a Celtic group. He REALLY needs to learn what one of these things can do for his sound. Here’s an irony, when I took the resonator off the back of this one to get photos for this article, I realized that the bolt holding the coordinating rod to the neck was completely loose. After I adjusted that, the thing held better tune. But now the action’s too low. It’s always something. 🙂

But what about the little cheapy you know the one I had so much trouble setting up, but which was so much fun when it settled in? The jury’s still out. I don’t really need a 4-string banjo. But it is fun to play. And is seven banjos REALLY too many?

Hi Paul,

thanks for the great article. I’d love to see / hear more about your Jameson banjo re-work. I’ve got one of those and I’m itching to tear the thing down and put it back together more usable than before.

Jason, thanks for chiming in. Is your Jameson a 5-string? One reason I had to do so much work on my Davison 6-string banjo is that it was built for a lefty. So I cut a new nut and ordered a new bridge. If you DON’T have to convert a banjo from left to right, and the neck is straight (or at least bowed evenly) the main things are usually tightening the head, adjusting the neck, and restringing the thing, according to the instructions here: https://creekdontrise.com/tabs_instr/banjo_tabs/setting_up/setting_up_five_string_banjo.htm If you can’t get the link to work, just google “setting up a five-string banjo” and it will come up on the first page.

Don’t bother adjusting the neck or even changing the strings until you’re sure the head is tight enough. There should be hardly any “dip” under the bridge. If it’s perfectly flat, you may have gone too far. Thank goodness your banjo head is made out of mylar these days, instead of skin, because people used to have blowouts that way. A head that is too loose lets the bridge sit too low, so the strings lay on the fretboard.

There is a VERY slim chance that the banjo’s neck meets the pot at the wrong angle, but adjust everything else to the best of your ability before you tinker with that. Adjusting the neck angle on a banjo with a single coordinating rod can get dicey, so be very careful when tightening or loosening that rod. I wouldn’t go more than a quarter of a turn at a time and give the banjo time to “settle in” before any further adjustment.

I WOULD recommend getting a compensated bridge (even a cheap imported one) since the “low” G string goes out of tune when fretted on most 5-strings, even my good ones. Deering tells me it’s my fault because I’m fretting the strings too hard, but I also play 12-string guitar so what can I say? Measure the height of your bridge before you order one, because both 1/2″ and 5/8″ bridges are popular.

If you feel the strings are too high at the nut, you can get an auto feeler gauge (they used to use them to measure the gap on spark plugs) and measure the height of the first fret. I use a triangular file to adjust the slots on the nut, but you may be able to trim what you need with a nail file. Be VERY careful. If you go down too far, you may still be able to salvage the nut by putting a dot of epoxy in the slot and starting again (I had do this on a banjo someone else “fixed”), but it’s not optimum.

In other words, if your Jameson is more-or-less playable now, the main thing is to make minor adjustments and keep tweaking it a little at a time until you’ve got it as playable as it can be. Best of luck, and let me know how things work out!