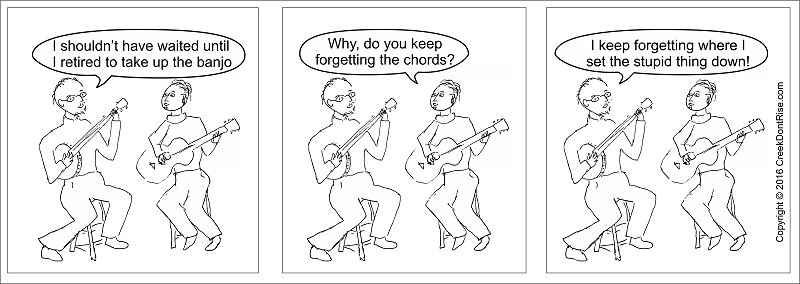

Yesterday I wrote and published a bit about why everyone interested in any kind of musical pursuits should learn a chord-capable instrument (probably piano or guitar) early. That article is on the SchoolOfTheRock.com site here. But musing over that content reminded me of something that happened to me a few days earlier.

I’ve addressed this topic somewhat in my blog “How Long do You Expect to Live, Anyway?” but this week’s experience brought it home to me anew.

I was practicing five-string banjo for an upcoming “gig.” It will be a banjo-only gig, but there might be some folk fans there, so I tried playing a few folk-style songs on banjo that I can just about do in my sleep on guitar.

It’s not hard to play such songs in D on the banjo using Raised Fifth Tuning. But when I tried a few songs I hadn’t tried in that key on banjo before, I realized to my surprise that I was having to think about the chords I was playing, something I haven’t done on guitar for songs of this type for maybe forty-five years.

What was the difference? When I was young, I played guitar so much that I internalized the chord changes for the keys of D, A, E, G, C, Em, and Am. After all these years, my fingers go on “autopilot” when I play folk-style songs in those keys.

But I never really internalized keys other than G and C on the banjo. So while I can play in keys like D, A, and Em, I can’t put my fingers on “autopilot” like I can on guitar.

This must be what it’s like for all my friends who “play guitar,” but have to think about the chord changes the first time through simple songs, and maybe even memorize them “by rote.” It’s one of those handicaps that people don’t realize they even have. And it’s one that was entirely avoidable at one point in their lives. If you’re under thirty, it’s probably avoidable in yours. If you’re under twenty, it’s certainly avoidable.

You understand that I’m not bragging, only saying that I am realizing too late how much better a musician I would have been at every stage in my life if I had had worked as hard on, say, voice and piano as I worked on guitar, and if I had worked on guitar harder than I did.

To me the “Holy Grail” of instrument accompaniment would be if I could sit down at the piano and accompany myself with a real piano part (not just banged chords) on almost any tune without thinking about it. Don’t laugh, I have friends who can do just that. But they started taking lessons when they were little and they kept playing and practicing their whole lives. As for me, I started trying to learn piano when I was about seventeen, and I gave up on any sort of formal instruction by the time I was nineteen. So I can memorize the piano parts of most piano/vocal arrangements well enough to play them if I have to, but mostly my piano playing is somewhere just this side of Paul McCartney’s playing on “Hey Jude.”

All is not lost – I can, technically, still play the piano to some extent. And if I put a little more practice time into playing those key-of-D songs on my banjo, they’ll eventually sink in. But something like 70% of my core skills on all of the instruments I play reasonably well were acquired by the time I was twenty-five, and the rest have mostly just built on those skills.

In other words, investing early in musical skills – even ones you think are boring or that you’ll never need – is crucial to long-term involvement in music, much less success. Spoken by the expert on “what not to do.” 🙂

Best of luck, and keep in touch,

Paul

Sadly, there is a lot of truth to this. I say sadly, because I’m even older than the author, which leaves me even more years to have regrets about! Educational theories come and go, a lot of them so that publishing companies and authors and editors can make colleges throw out all the old texts and have to buy new ones.

When I was in graduate school, back when dinosaurs still roamed the earth and the earth’s crust was still cooling, the rage was – forget the “disciplines,” the math, the music. It doesn’t matter what you study, whether “The Brothers Karamazov” or the manual to the washing machine. The brain is like a cellulose sponge and it all just mushes around in there.

I suspected it was hogwash then, and we know it’s hogwash now. The disciplines are where it’s at, because each bit of knowledge or skill we acquire, mentally, emotionally or kinetically, has its own special places in our brain. Musicians and athletes can talk about “muscle memory” and know it is real. The drive to the basket, learning a second language, the move from C major to B7, the mental habit of assuming malice on the part of a stranger, crocheting an afghan, bringing the thumb under the third finger in an ascending C scale – “Use it or lose it.”

We had chances when we were young and we missed out on them, either for lack of opportunity, or resistance to practice, or distraction. Those were the very first chances we had to grow. And the skills we picked up when our brain was a NEW sponge became part of the air we breathe. The skills I pick up now, when my brain could use a good run through the dishwasher, come harder.

The list of things I’ll never be is pretty long – ballerina, concert pianist, anything involving random number tables, for starters. But the list of things I can never do is shorter. I can put on a leotard and go to an adult class and laugh with everyone else, I can practice my scales, I can take a free online math class at the Khan Academy.

I just have to accept that the book shelves which were so empty and new and fillable when I was eight are now dusty, cluttered, and sagging. But a year ago I picked up the guitar again after some years, and determined to practice every day. I started at ten minutes, have worked up to twenty. My fingers get sore, my joints won’t cooperate, my skill level is pretty elementary and it sounds like it. But I can accompany my singing, and I have developed/renewed a repertoire of about fifty songs in four different languages, at least seventy-five percent of which I would not be afraid to haul out and play for a friend.

I guess that’s something. Learn now. If you can arrange to be younger again, learn then. But in the absence of time travel, learn now.